How Long Was The Battle Of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings [a] was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Knuckles of Normandy, and an English language regular army nether the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conquest of England. It took place approximately vii mi (11 km) northwest of Hastings, close to the present-twenty-four hour period town of Boxing, Due east Sussex, and was a decisive Norman victory.

The background to the battle was the decease of the childless King Edward the Confessor in Jan 1066, which prepare a succession struggle between several claimants to his throne. Harold was crowned king shortly after Edward'south death, but faced invasions by William, his own blood brother Tostig, and the Norwegian King Harald Hardrada (Harold III of Norway). Hardrada and Tostig defeated a hastily gathered army of Englishmen at the Battle of Fulford on 20 September 1066, and were in plough defeated past Harold at the Boxing of Stamford Span five days afterward. The deaths of Tostig and Hardrada at Stamford Bridge left William as Harold's only serious opponent. While Harold and his forces were recovering, William landed his invasion forces in the south of England at Pevensey on 28 September 1066 and established a beachhead for his conquest of the kingdom. Harold was forced to march southward swiftly, gathering forces as he went.

The verbal numbers present at the battle are unknown equally fifty-fifty modern estimates vary considerably. The limerick of the forces is clearer: the English army was composed almost entirely of infantry and had few archers, whereas but virtually half of the invading force was infantry, the balance split equally between cavalry and archers. Harold appears to have tried to surprise William, only scouts found his regular army and reported its arrival to William, who marched from Hastings to the battlefield to face Harold. The battle lasted from most 9 am to dusk. Early efforts of the invaders to break the English battle lines had piddling result. Therefore, the Normans adopted the tactic of pretending to flee in panic and then turning on their pursuers. Harold'southward decease, probably near the end of the battle, led to the retreat and defeat of most of his army. After further marching and some skirmishes, William was crowned equally king on Christmas Twenty-four hour period 1066.

There continued to be rebellions and resistance to William's rule, merely Hastings effectively marked the culmination of William's conquest of England. Casualty figures are difficult to come up by, merely some historians estimate that ii,000 invaders died along with nigh twice that number of Englishmen. William founded a monastery at the site of the boxing, the high altar of the abbey church supposedly placed at the spot where Harold died.

Background

In 911, the Carolingian ruler Charles the Elementary allowed a group of Vikings to settle in Normandy under their leader Rollo.[1] Their settlement proved successful,[2] [b] and they apace adjusted to the ethnic civilization, renouncing paganism, converting to Christianity,[3] and intermarrying with the local population.[4] Over time, the frontiers of the duchy expanded to the west.[5] In 1002, King Æthelred 2 married Emma, the sis of Richard II, Duke of Normandy.[vi] Their son Edward the Confessor spent many years in exile in Normandy, and succeeded to the English throne in 1042.[7] This led to the establishment of a powerful Norman interest in English politics, as Edward drew heavily on his onetime hosts for support, bringing in Norman courtiers, soldiers, and clerics and appointing them to positions of ability, particularly in the Church. Edward was childless and embroiled in conflict with the formidable Godwin, Earl of Wessex, and his sons, and he may also have encouraged Knuckles William of Normandy's ambitions for the English throne.[8]

Succession crisis in England

King Edward's death on 5 January 1066[9] [c] left no clear heir, and several contenders laid claim to the throne of England.[11] Edward's immediate successor was the Earl of Wessex, Harold Godwinson, the richest and most powerful of the English aristocrats and son of Godwin, Edward'southward earlier opponent. Harold was elected rex by the Witenagemot of England and crowned by Ealdred, the Archbishop of York, although Norman propaganda claimed that the ceremony was performed by Stigand, the uncanonically elected Archbishop of Canterbury.[11] [12] Harold was at once challenged by two powerful neighbouring rulers. Knuckles William claimed that he had been promised the throne by Male monarch Edward and that Harold had sworn agreement to this.[13] Harald Hardrada of Norway besides contested the succession. His merits to the throne was based on an agreement between his predecessor Magnus the Skillful and the before King of England Harthacnut, whereby, if either died without heir, the other would inherit both England and Norway.[fourteen] William and Harald Hardrada immediately set most assembling troops and ships for split invasions.[xv] [d]

Tostig and Hardrada's invasions

In early 1066, Harold's exiled brother Tostig Godwinson raided southeastern England with a fleet he had recruited in Flanders, later joined by other ships from Orkney. Threatened past Harold'due south fleet, Tostig moved north and raided in East Anglia and Lincolnshire. He was driven back to his ships by the brothers Edwin, Earl of Mercia and Morcar, Earl of Northumbria. Deserted by about of his followers, he withdrew to Scotland, where he spent the middle of the year recruiting fresh forces.[21] Hardrada invaded northern England in early September, leading a armada of more than than 300 ships carrying perhaps 15,000 men. Hardrada's ground forces was further augmented by the forces of Tostig, who supported the Norwegian king's bid for the throne. Advancing on York, the Norwegians occupied the city after defeating a northern English language regular army nether Edwin and Morcar on 20 September at the Battle of Fulford.[22]

English army and Harold's preparations

The English army was organised along regional lines, with the fyrd, or local levy, serving under a local magnate – whether an earl, bishop, or sheriff.[23] The fyrd was equanimous of men who owned their own country, and were equipped by their community to fulfil the king's demands for military forces. For every five hides,[24] or units of land nominally capable of supporting one household,[25] one homo was supposed to serve.[24] It appears that the hundred was the principal organising unit for the fyrd.[26] As a whole, England could replenish most 14,000 men for the fyrd, when it was called out. The fyrd commonly served for two months, except in emergencies. Information technology was rare for the whole national fyrd to be called out; between 1046 and 1065 information technology was merely done three times, in 1051, 1052, and 1065.[24] The king besides had a group of personal armsmen, known as housecarls, who formed the courage of the royal forces. Some earls also had their own forces of housecarls. Thegns, the local landowning elites, either fought with the royal housecarls or attached themselves to the forces of an earl or other magnate.[23] The fyrd and the housecarls both fought on foot, with the major difference between them being the housecarls' superior armour. The English army does not appear to have had a meaning number of archers.[26]

Harold had spent mid-1066 on the south coast with a large army and fleet waiting for William to invade. The bulk of his forces were militia who needed to harvest their crops, so on 8 September Harold dismissed the militia and the fleet.[27] Learning of the Norwegian invasion he rushed north, gathering forces as he went, and took the Norwegians past surprise, defeating them at the Boxing of Stamford Bridge on 25 September. Harald Hardrada and Tostig were killed, and the Norwegians suffered such nifty losses that only 24 of the original 300 ships were required to comport away the survivors. The English language victory came at bang-up cost, as Harold's regular army was left in a dilapidated and weakened land, and far from the southward.[28]

William'due south preparations and landing

On landing at Pevensey, William established a castle within the ruins of the Roman fort. While the outermost walls date from the Roman period, the surviving buildings of the inner bailey mail-date William.[29]

William assembled a large invasion armada and an army gathered from Normandy and the rest of France, including large contingents from Brittany and Flanders.[30] He spent about nine months on his preparations, as he had to construct a fleet from zero.[e] According to some Norman chronicles, he also secured diplomatic support, although the accuracy of the reports has been a matter of historical debate. The most famous merits is that Pope Alexander Ii gave a papal imprint every bit a token of support, which simply appears in William of Poitiers'southward account, and not in more contemporary narratives.[33] In Apr 1066 Halley'south Comet appeared in the sky, and was widely reported throughout Europe. Contemporary accounts continued the comet's appearance with the succession crunch in England.[34] [f]

William mustered his forces at Saint-Valery-sur-Somme, and was ready to cross the English Aqueduct by about 12 Baronial.[36] But the crossing was delayed, either considering of unfavourable weather condition or to avoid beingness intercepted by the powerful English language fleet. The Normans crossed to England a few days after Harold's victory over the Norwegians, following the dispersal of Harold's naval force, and landed at Pevensey in Sussex on 28 September.[30] [grand] [h] A few ships were blown off course and landed at Romney, where the Normans fought the local fyrd.[32] Later on landing, William's forces built a wooden castle at Hastings, from which they raided the surrounding expanse.[30] More fortifications were erected at Pevensey.[51]

Norman forces at Hastings

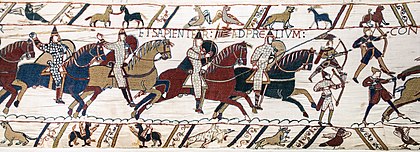

Norman knights and archers at the Boxing of Hastings, every bit depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry

The verbal numbers and composition of William's force are unknown.[31] A contemporary document claims that William had 776 ships, just this may be an inflated figure.[52] Figures given by contemporary writers for the size of the army are highly exaggerated, varying from 14,000 to 150,000.[53] Mod historians have offered a range of estimates for the size of William's forces: 7,000–8,000 men, ane,000–2,000 of them cavalry;[54] x,000–12,000 men;[53] x,000 men, three,000 of them cavalry;[55] or 7,500 men.[31] The army consisted of cavalry, infantry, and archers or crossbowmen, with about equal numbers of cavalry and archers and the foot soldiers equal in number to the other two types combined.[56] Later lists of companions of William the Conqueror are extant, only most are padded with extra names; only about 35 named individuals can be reliably identified as having been with William at Hastings.[31] [57] [i]

The principal armour used was chainmail hauberks, usually knee-length, with slits to allow riding, some with sleeves to the elbows. Some hauberks may have been made of scales attached to a tunic, with the scales fabricated of metallic, horn or hardened leather. Headgear was usually a conical metal helmet with a band of metal extending down to protect the nose.[59] Horsemen and infantry carried shields. The infantryman's shield was commonly round and made of wood, with reinforcement of metal. Horsemen had inverse to a kite-shaped shield and were commonly armed with a lance. The couched lance, carried tucked confronting the body under the correct arm, was a relatively new refinement and was probably non used at Hastings; the terrain was unfavourable for long cavalry charges. Both the infantry and cavalry usually fought with a straight sword, long and double-edged. The infantry could also use javelins and long spears.[60] Some of the cavalry may take used a mace instead of a sword. Archers would have used a cocky bow or a crossbow, and nigh would not have had armour.[61]

Harold moves southward

After defeating his brother Tostig and Harald Hardrada in the due north, Harold left much of his forces in the due north, including Morcar and Edwin, and marched the rest of his army south to deal with the threatened Norman invasion.[62] It is unclear when Harold learned of William's landing, just it was probably while he was travelling southward. Harold stopped in London, and was there for about a week earlier Hastings, so it is likely that he spent virtually a week on his march south, averaging about 27 mi (43 km) per day,[63] for the approximately 200 mi (320 km).[64] Harold camped at Caldbec Hill on the dark of 13 October, near what was described equally a "hoar-apple tree tree". This location was well-nigh 8 mi (13 km) from William's castle at Hastings.[65] [j] Some of the early gimmicky French accounts mention an emissary or emissaries sent by Harold to William, which is probable. Aught came of these efforts.[66]

Although Harold attempted to surprise the Normans, William's scouts reported the English arrival to the duke. The exact events preceding the battle are obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy.[66] Harold had taken a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (nowadays-day Battle, East Sussex), about 6 mi (9.7 km) from William's castle at Hastings.[67]

English language forces at Hastings

The exact number of soldiers in Harold'southward army is unknown. The contemporary records do non give reliable figures; some Norman sources give 400,000 to 1,200,000 men on Harold's side.[yard] The English sources generally requite very low figures for Harold's army, possibly to make the English defeat seem less devastating.[69] Recent historians take suggested figures of betwixt 5,000 and 13,000 for Harold's army at Hastings,[70] and virtually modern historians fence for a figure of seven,000–8,000 English troops.[26] [71] These men would have been a mix of the fyrd and housecarls. Few individual Englishmen are known to have been at Hastings;[31] about 20 named individuals can reasonably be causeless to have fought with Harold at Hastings, including Harold's brothers Gyrth and Leofwine and two other relatives.[58] [fifty]

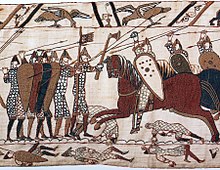

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry depicting mounted Norman soldiers attacking Anglo-Saxons who are fighting on human foot in a shield wall

The English language regular army consisted entirely of infantry. It is possible that some of the higher course members of the ground forces rode to battle, but when battle was joined they dismounted to fight on foot.[m] The core of the ground forces was made up of housecarls, full-time professional soldiers. Their armour consisted of a conical helmet, a mail hauberk, and a shield, which might be either kite-shaped or round.[72] Almost housecarls fought with the two-handed Danish battleaxe, but they could also behave a sword.[73] The residue of the army was made upward of levies from the fyrd, also infantry simply more lightly armoured and not professionals. Most of the infantry would have formed function of the shield wall, in which all the men in the front end ranks locked their shields together. Behind them would accept been axemen and men with javelins as well as archers.[74]

Boxing

Background and location

The battlefield from the northward side

Because many of the main accounts contradict each other at times, it is impossible to provide a description of the battle that is across dispute.[75] The only undisputed facts are that the fighting began at nine am on Saturday 14 October 1066 and that the boxing lasted until dusk.[76] Sunset on the day of the battle was at 4:54 pm, with the battlefield mostly dark by 5:54 pm and in total darkness past 6:24 pm. Moonrise that nighttime was non until 11:12 pm, so once the sun ready, there was trivial light on the battlefield.[77] William of Jumièges reports that Duke William kept his army armed and prepare against a surprise night attack for the entire dark before.[75] The battle took place 7 mi (11 km) north of Hastings at the present-day boondocks of Boxing,[78] between two hills – Caldbec Hill to the n and Telham Hill to the due south. The area was heavily wooded, with a marsh nearby.[79] The proper name traditionally given to the battle is unusual – in that location were several settlements much closer to the battlefield than Hastings. The Anglo-Saxon Relate called it the battle "at the hoary apple tree". Within forty years, the battle was described past the Anglo-Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis equally "Senlac",[due north] a Norman-French adaptation of the Erstwhile English discussion "Sandlacu", which ways "sandy h2o".[o] This may take been the proper noun of the stream that crosses the battleground.[p] The battle was already being referred to as "bellum Haestingas" or "Boxing of Hastings" by 1086, in the Domesday Book.[83]

Sunrise was at 6:48 am that morning, and reports of the 24-hour interval record that it was unusually brilliant.[84] The atmospheric condition conditions are not recorded.[85] The route that the English army took south to the battleground is non known precisely. Several roads are possible: one, an old Roman road that ran from Rochester to Hastings has long been favoured considering of a large money hoard found nearby in 1876. Another possibility is the Roman road between London and Lewes and and so over local tracks to the battlefield.[75] Some accounts of the battle indicate that the Normans advanced from Hastings to the battlefield, but the contemporary account of William of Jumièges places the Normans at the site of the battle the night before.[86] Most historians incline towards the former view,[67] [84] [87] [88] simply G. Thou. Lawson argues that William of Jumièges'due south account is right.[86]

Dispositions of forces and tactics

Harold's forces deployed in a small, dense formation at the top of steep slope,[84] with their flanks protected past woods and marshy footing in front of them.[88] The line may have extended far enough to exist anchored on a nearby stream.[89] The English formed a shield wall, with the forepart ranks holding their shields shut together or even overlapping to provide protection from attack.[90] Sources differ on the verbal site that the English fought on: some sources state the site of the abbey,[91] [92] [93] but some newer sources propose information technology was Caldbec Hill.[89] [84]

More than is known about the Norman deployment.[94] Duke William appears to take arranged his forces in 3 groups, or "battles", which roughly corresponded to their origins. The left units were the Bretons,[95] forth with those from Anjou, Poitou and Maine. This division was led past Alan the Cherry-red, a relative of the Breton count.[90] The centre was held past the Normans,[95] under the direct command of the duke and with many of his relatives and kinsmen grouped around the ducal party.[xc] The last division, on the correct, consisted of the Frenchmen,[95] forth with some men from Picardy, Boulogne, and Flemish region. The right was allowable by William fitzOsbern and Count Eustace II of Boulogne.[ninety] The front lines were made up of archers, with a line of foot soldiers armed with spears backside.[95] In that location were probably a few crossbowmen and slingers in with the archers.[xc] The cavalry was held in reserve,[95] and a modest group of clergymen and servants situated at the base of Telham Hill was not expected to take office in the fighting.[90]

William'due south disposition of his forces implies that he planned to open the battle with archers in the front end rank weakening the enemy with arrows, followed by infantry who would engage in close combat. The infantry would create openings in the English lines that could be exploited by a cavalry accuse to break through the English forces and pursue the fleeing soldiers.[90]

Starting time of the battle

The battle opened with the Norman archers shooting uphill at the English shield wall, to little effect. The uphill angle meant that the arrows either bounced off the shields of the English language or overshot their targets and flew over the top of the hill.[95] [q] The lack of English archers hampered the Norman archers, as there were few English arrows to be gathered upwards and reused.[96] Later on the attack from the archers, William sent the spearmen forrad to assail the English. They were met with a barrage of missiles, not arrows just spears, axes and stones.[95] The infantry was unable to force openings in the shield wall, and the cavalry advanced in support.[96] The cavalry also failed to brand headway, and a full general retreat began, blamed on the Breton segmentation on William's left.[97] A rumour started that the duke had been killed, which added to the confusion. The English forces began to pursue the fleeing invaders, simply William rode through his forces, showing his face and yelling that he was still alive.[98] The duke then led a counter-attack against the pursuing English forces; some of the English rallied on a hillock before beingness overwhelmed.[97]

It is not known whether the English pursuit was ordered by Harold or if information technology was spontaneous. Wace relates that Harold ordered his men to stay in their formations but no other account gives this detail. The Bayeux Tapestry depicts the death of Harold's brothers Gyrth and Leofwine occurring merely before the fight around the hillock. This may hateful that the two brothers led the pursuit.[99] The Carmen de Hastingae Proelio relates a different story for the death of Gyrth, stating that the knuckles slew Harold's blood brother in combat, perhaps thinking that Gyrth was Harold. William of Poitiers states that the bodies of Gyrth and Leofwine were found most Harold's, implying that they died late in the battle. It is possible that if the two brothers died early on in the fighting their bodies were taken to Harold, thus accounting for their being found about his torso subsequently the battle. The military machine historian Peter Marren speculates that if Gyrth and Leofwine died early on in the boxing, that may take influenced Harold to stand and fight to the end.[100]

Feigned flights

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing mounted Norman cavalrymen fighting Anglo-Saxon infantry

A lull probably occurred early in the afternoon, and a interruption for rest and food would probably accept been needed.[99] William may take also needed time to implement a new strategy, which may have been inspired past the English pursuit and subsequent rout by the Normans. If the Normans could send their cavalry against the shield wall so depict the English into more pursuits, breaks in the English line might form.[101] William of Poitiers says the tactic was used twice. Although arguments have been made that the chroniclers' accounts of this tactic were meant to excuse the flight of the Norman troops from boxing, this is unlikely every bit the earlier flight was not glossed over. It was a tactic used past other Norman armies during the period.[99] [r] Some historians have argued that the story of the use of feigned flight equally a deliberate tactic was invented after the boxing; however most historians concur that information technology was used by the Normans at Hastings.[102]

Although the feigned flights did not break the lines, they probably thinned out the housecarls in the English shield wall. The housecarls were replaced with members of the fyrd, and the shield wall held.[99] Archers appear to have been used over again before and during an set on by the cavalry and infantry led by the duke. Although 12th-century sources land that the archers were ordered to shoot at a high angle to shoot over the front of the shield wall, there is no trace of such an activeness in the more contemporary accounts.[103] Information technology is not known how many assaults were launched confronting the English lines, just some sources record various actions by both Normans and Englishmen that took place during the afternoon'south fighting.[104] The Carmen claims that Duke William had two horses killed under him during the fighting, but William of Poitiers'due south business relationship states that it was 3.[105]

Expiry of Harold

Stone marking the spot of the high altar at Boxing Abbey, where Harold died[106]

Harold appears to have died late in the battle, although accounts in the various sources are contradictory. William of Poitiers only mentions his expiry, without giving any details on how information technology occurred. The Tapestry is not helpful, every bit information technology shows a figure holding an arrow sticking out of his heart next to a falling fighter beingness hit with a sword. Over both figures is a statement "Hither King Harold has been killed".[103] Information technology is not clear which figure is meant to be Harold, or if both are meant.[107] [s] The primeval written mention of the traditional account of Harold dying from an arrow to the eye dates to the 1080s from a history of the Normans written by an Italian monk, Amatus of Montecassino.[108] [t] William of Malmesbury stated that Harold died from an arrow to the middle that went into the brain, and that a knight wounded Harold at the aforementioned fourth dimension. Wace repeats the arrow-to-the-center account. The Carmen states that Knuckles William killed Harold, just this is unlikely, as such a feat would take been recorded elsewhere.[103] The business relationship of William of Jumièges is even more unlikely, equally it has Harold dying in the forenoon, during the first fighting. The Chronicle of Battle Abbey states that no one knew who killed Harold, as information technology happened in the printing of battle.[110] A mod biographer of Harold, Ian Walker, states that Harold probably died from an arrow in the center, although he also says it is possible that Harold was struck down by a Norman knight while mortally wounded in the eye.[111] Some other biographer of Harold, Peter Rex, after discussing the various accounts, concludes that it is not possible to declare how Harold died.[109]

Harold's death left the English forces leaderless, and they began to collapse.[101] Many of them fled, merely the soldiers of the royal household gathered around Harold's torso and fought to the end.[103] The Normans began to pursue the fleeing troops, and except for a rearguard activity at a site known as the "Malfosse", the battle was over.[101] Exactly what happened at the Malfosse, or "Evil Ditch", and where it took place, is unclear. It occurred at a small fortification or set of trenches where some Englishmen rallied and seriously wounded Eustace of Boulogne before existence defeated by the Normans.[112]

Reasons for the effect

Harold'southward defeat was probably due to several circumstances. One was the demand to defend against two near simultaneous invasions. The fact that Harold had dismissed his forces in southern England on 8 September also contributed to the defeat. Many historians fault Harold for hurrying south and non gathering more forces before confronting William at Hastings, although it is non clear that the English forces were insufficient to deal with William's forces.[113] Against these arguments for an exhausted English army, the length of the battle, which lasted an unabridged twenty-four hours, shows that the English forces were not tired by their long march.[114] Tied in with the speed of Harold's accelerate to Hastings is the possibility Harold may not have trusted Earls Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria one time their enemy Tostig had been defeated, and declined to bring them and their forces south.[113] Modern historians accept pointed out that ane reason for Harold's rush to boxing was to incorporate William's depredations and continue him from breaking free of his beachhead.[115]

Most of the arraign for the defeat probably lies in the events of the boxing.[113] William was the more experienced military leader,[116] and in improver the lack of cavalry on the English side allowed Harold fewer tactical options.[114] Some writers take criticised Harold for not exploiting the opportunity offered by the rumoured death of William early in the boxing.[117] The English appear to have erred in not staying strictly on the defensive, for when they pursued the retreating Normans they exposed their flanks to attack. Whether this was due to the inexperience of the English commanders or the indiscipline of the English soldiers is unclear.[116] [u] In the terminate, Harold's death appears to have been decisive, as it signalled the break-upward of the English forces in disarray.[114] The historian David Nicolle said of the boxing that William'south army "demonstrated – non without difficulty – the superiority of Norman-French mixed cavalry and infantry tactics over the Germanic-Scandinavian infantry traditions of the Anglo-Saxons."[119]

Aftermath

Ruins of the monks' dormitory at Battle Abbey

The day later the battle, Harold's body was identified, either past his armour or by marks on his body.[v] His personal standard was presented to William,[120] and later on sent to the papacy.[103] The bodies of the English dead, including some of Harold's brothers and housecarls, were left on the battlefield,[121] although some were removed by relatives later.[122] The Norman dead were buried in a big communal grave, which has not been found.[123] [w] Exact casualty figures are unknown. Of the Englishmen known to be at the battle, the number of expressionless implies that the expiry rate was about 50 per cent of those engaged, although this may be as well loftier. Of the named Normans who fought at Hastings, 1 in seven is stated to take died, merely these were all noblemen, and it is probable that the death rate among the common soldiers was higher. Although Orderic Vitalis'due south figures are highly exaggerated,[x] his ratio of one in four casualties may exist authentic. Marren speculates that perhaps ii,000 Normans and 4,000 Englishmen were killed at Hastings.[124] Reports stated that some of the English dead were yet being plant on the hillside years later on. Although scholars idea for a long time that remains would not be recoverable, due to the acidic soil, contempo finds accept changed this view.[125] One skeleton that was found in a medieval cemetery, and originally was thought to be associated with the 13th century Battle of Lewes, at present is thought to be associated with Hastings instead.[126] [y]

1 story relates that Gytha, Harold's mother, offered the victorious knuckles the weight of her son's body in gold for its custody, but was refused. William ordered that Harold's body exist thrown into the ocean, but whether that took identify is unclear.[121] Another story relates that Harold was buried at the top of a cliff.[123] Waltham Abbey, which had been founded by Harold, afterwards claimed that his torso had been secretly cached in that location.[121] Other legends claimed that Harold did not die at Hastings, but escaped and became a hermit at Chester.[122]

William expected to receive the submission of the surviving English leaders after his victory, but instead Edgar the Ætheling[z] was proclaimed king by the Witenagemot, with the support of Earls Edwin and Morcar, Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Ealdred, the Archbishop of York.[128] William therefore advanced on London, marching around the coast of Kent. He defeated an English force that attacked him at Southwark simply was unable to storm London Bridge, forcing him to reach the capital letter by a more complex route.[129]

William moved up the Thames valley to cross the river at Wallingford, where he received the submission of Stigand. He and so travelled northward-due east along the Chilterns, before advancing towards London from the north-w,[aa] fighting further engagements confronting forces from the city. The English leaders surrendered to William at Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. William was acclaimed King of England and crowned by Ealdred on 25 December 1066, in Westminster Abbey.[129]

Despite the submission of the English nobles, resistance continued for several years.[131] In that location were rebellions in Exeter in late 1067, an invasion past Harold'southward sons in mid-1068, and an uprising in Northumbria in 1068.[132] In 1069 William faced more troubles from Northumbrian rebels, an invading Danish fleet, and rebellions in the s and west of England. He ruthlessly put downwardly the various risings, culminating in the Harrying of the North in belatedly 1069 and early 1070 that devastated parts of northern England.[133] A further rebellion in 1070 by Hereward the Wake was likewise defeated by the king, at Ely.[134]

Battle Abbey was founded by William at the site of the boxing. Co-ordinate to 12th-century sources, William made a vow to found the abbey, and the loftier chantry of the church building was placed at the site where Harold had died.[101] More than likely, the foundation was imposed on William by papal legates in 1070.[135] The topography of the battleground has been altered by subsequent construction work for the abbey, and the gradient dedicated by the English language is now much less steep than it was at the time of the battle; the top of the ridge has also been built up and levelled.[78] After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the abbey's lands passed to secular landowners, who used it as a residence or state business firm.[136] In 1976 the estate was put upwardly for sale and purchased by the government with the help of some American donors who wished to award the 200th anniversary of American independence.[137] The battleground and abbey grounds are currently endemic and administered by English Heritage and are open up to the public.[138] The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidered narrative of the events leading up to Hastings probably commissioned by Odo of Bayeux soon afterwards the boxing, peradventure to hang at the bishop's palace at Bayeux.[139] [ab] In modern times annual reenactments of the Boxing of Hastings take drawn thousands of participants and spectators to the site of the original boxing.[141] [142]

See likewise

- Ermenfrid Penitential

Notes

- ^ Erstwhile English: Gefeoht æt Hæstingum Norman: Batâle dé Hastings

- ^ The Vikings in the region became known as the "Northmen", from which "Normandy" and "Normans" are derived.[ii]

- ^ There is some slight confusion in the original sources near the exact engagement; it was well-nigh likely 5 January, but a few contemporaneous sources give 4 January.[10]

- ^ Other contenders later on came to the fore. The get-go was Edgar Ætheling, Edward the Confessor's nifty nephew who was a patrilineal descendant of King Edmund Ironside. He was the son of Edward the Exile, son of Edmund Ironside, and was born in Hungary where his father had fled after the conquest of England by Cnut the Great. After his family's eventual return to England and his father'due south death in 1057,[16] Edgar had by far the strongest hereditary claim to the throne, merely he was but well-nigh thirteen or fourteen at the fourth dimension of Edward the Confessor's expiry, and with lilliputian family to support him, his claim was passed over past the Witenaġemot.[17] Another contender was Sweyn II of Kingdom of denmark, who had a claim to the throne as the grandson of Sweyn Forkbeard and nephew of Cnut,[18] just he did not make his bid for the throne until 1069.[19] Tostig Godwinson'due south attacks in early 1066 may have been the commencement of a bid for the throne, just threw in his lot with Harald Hardrada after defeat at the easily of Edwin and Morcar and the desertion of most of his followers he.[xx]

- ^ The surviving transport list gives 776 ships, contributed by 14 different Norman nobles.[31] This listing does not include William's flagship, the Mora, given to him past his wife, Matilda of Flanders. The Mora is depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry with a panthera leo figurehead.[32]

- ^ The comet's appearance was depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry, where information technology is connected with Harold's coronation, although the appearance of the comet was after, from 24 Apr to i May 1066. The prototype on the tapestry is the earliest pictorial depiction of Halley's Comet to survive.[35]

- ^ Most modern historians agree on this appointment,[37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] although a few gimmicky sources accept William landing on 29 September.[43]

- ^ Well-nigh contemporary accounts take William landing at Pevensey, with only the E version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle giving the landing equally taking place at Hastings.[43] Nigh mod accounts likewise state that William's forces landed at Pevensey.[32] [38] [39] [xl] [41] [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50]

- ^ Of those 35, 5 are known to have died in the battle: Robert of Vitot, Engenulf of Laigle, Robert fitzErneis, Roger son of Turold, and Taillefer.[58]

- ^ "Hoar" means grey, and probably refers to a crab-apple tree covered with lichen that was probable a local landmark.[65]

- ^ The 400,000 figure is given in Wace's Romance de Rou and the 1,200,000 effigy coming from the Carmen de Hastingae Proelio.[68]

- ^ Of these named persons, eight died in the battle – Harold, Gyrth, Leofwine, Godric the sheriff, Thurkill of Berkshire, Breme, and someone known only as "son of Helloc".[58]

- ^ Some historians have argued, based on comments by Snorri Sturlson made in the 13th century, that the English army did occasionally fight as cavalry. Contemporary accounts, such as in the Anglo-Saxon Relate record that when English soldiers were forced to fight on horseback, they were normally routed, as in 1055 near Hereford.[72]

- ^ This was the name popularised past Edward Freeman,[80] a Victorian historian who wrote one of the definitive accounts of the boxing.[81]

- ^ "Sandlacu" can be rendered into Modern English as "sandlake".[lxxx]

- ^ Freeman suggested that "Senlac" meant "sand lake" in Old English with the Norman conquerors calling it (in French) "sanguelac". Freeman regarded this utilise as a pun because the English translation of "sanguelac" is "blood lake".[82]

- ^ There is a story that the first fighting at Hastings was between a jongleur named Taillefer and some of the English fighters which comes from three sources: the Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, Wace's Romance de Rou, and the 12th-century account of Henry of Huntingdon.[xc] The story has 2 versions, in one of which Taillefer entertained the Norman army prior to the boxing by juggling a sword but then killed an English language soldier sent to kill him. Another version has the jongleur charging the English and killing 2 before dying himself.[85]

- ^ Examples of the use of feigned flight include the Battle of Arques around 1052, the Battle of Messina in 1060, and the Battle of Cassel in 1071.[99]

- ^ The issue is further dislocated by the fact that in that location is evidence that the 19th-century restoration of the Tapestry inverse the scene past inserting or irresolute the placement of the arrow through the centre.[107]

- ^ Amatus' business relationship is less than trustworthy considering information technology likewise states that Knuckles William commanded 100,000 soldiers at Hastings.[109]

- ^ Modern wargaming has demonstrated the correctness of not pursuing the fleeing Normans,[115] with the historian Christopher Gravett stating that if in a wargame he allowed Harold to pursue the Normans, his opponent "promptly, and rightly, punished such rashness with a brisk counter-attack with proved to exist the turning point of the battle – just as in 1066".[118]

- ^ A 12th-century tradition stated that Harold's face up could not be recognised and Edith the Fair, Harold's common-law wife, was brought to the battlefield to identify his body from marks that but she knew.[112]

- ^ It is possible the grave site was located where the abbey now stands.[123]

- ^ He states that there were 15,000 casualties out of 60,000 who fought on William's side at the boxing.[124]

- ^ This skeleton, numbered 180, sustained six fatal sword cuts to the dorsum of the skull and was one of five skeletons that had suffered trigger-happy trauma. Assay continues on the other remains to try to build up a more accurate picture of who the individuals are.[125]

- ^ Ætheling is the Anglo-Saxon term for a royal prince with some claim to the throne.[127]

- ^ William appears to take taken this route to run into up with reinforcements that had landed past Portsmouth and met him between London and Winchester. Past swinging around to the north, William cutting off London from reinforcements.[130]

- ^ The first recorded mention of the tapestry is from 1476, just it is similar in style to late Anglo-Saxon manuscript illustrations and may have been equanimous and executed in England.[139] The Tapestry now is displayed at the former Bishop's Palace at Bayeux in France.[140]

Citations

- ^ Bates Normandy Before 1066 pp. viii–10

- ^ a b Crouch Normans pp. 15–sixteen

- ^ Bates Normandy Earlier 1066 p. 12

- ^ Bates Normandy Before 1066 pp. 20–21

- ^ Hallam and Everard Capetian France p. 53

- ^ Williams Æthelred the Unready p. 54

- ^ Huscroft Ruling England p. iii

- ^ Stafford Unification and Conquest pp. 86–99

- ^ Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 29

- ^ Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 250 and footnote 1

- ^ a b Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England pp. 167–181

- ^ Walker Harold pp. 136–138

- ^ Bates William the Conquistador pp. 73–77

- ^ Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England pp. 188–190

- ^ Huscroft Ruling England pp. 12–14

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 96–97

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 132–133

- ^ Stafford Unification and Conquest pp. 86–87

- ^ Bates William the Conquistador pp. 103–104

- ^ Thomas Norman Conquest pp. 33–34

- ^ Walker Harold pp. 144–145

- ^ Walker Harold pp. 154–158

- ^ a b Nicolle Medieval Warfare Sourcebook pp. 69–71

- ^ a b c Marren 1066 pp. 55–57

- ^ Coredon Lexicon of Medieval Terms and Phrases p. 154

- ^ a b c Gravett Hastings pp. 28–34

- ^ Walker Harold pp. 144–150

- ^ Walker Harold pp. 158–165

- ^ Porter Pevensey Castle pp. four, 26–27

- ^ a b c Bates William the Conqueror pp. 79–89

- ^ a b c d e Gravett Hastings pp. xx–21

- ^ a b c Marren 1066 pp. 91–92

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 120–122

- ^ Douglas William the Conquistador p. 181 and footnote ane

- ^ Musset Bayeux Tapestry p. 176

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 192

- ^ Gravett Hastings p. 50

- ^ a b Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 123

- ^ a b Barlow Feudal Kingdom p. 81

- ^ a b Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 591

- ^ a b Thomas Norman Conquest p. 35

- ^ Douglas William the Conquistador p. 195

- ^ a b Lawson Battle of Hastings p. 176

- ^ Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. 37

- ^ Gravett Hastings pp. 47–49

- ^ Huscroft Ruling England p. 15

- ^ Stafford Unification and Conquest p. 100

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 86

- ^ Walker Harold p. 166

- ^ Rex Harold II p. 221

- ^ Lawson Battle of Hastings p. 179

- ^ Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. 25

- ^ a b Lawson Hastings pp. 163–164

- ^ Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. 26

- ^ Marren 1066 pp. 89–90

- ^ Gravett Hastings p. 27

- ^ Marren 1066 pp. 108–109

- ^ a b c Marren 1066 pp. 107–108

- ^ Gravett Hastings pp. 15–19

- ^ Gravett Hastings p. 22

- ^ Gravett Hastings pp. 24–25

- ^ Carpenter Struggle for Mastery p. 72

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 93

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 124

- ^ a b Marren 1066 pp. 94–95

- ^ a b Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 180–182

- ^ a b Marren 1066 pp. 99–100

- ^ Lawson Battle of Hastings p. 128 footnote 32

- ^ Lawson Boxing of Hastings p. 128 and footnote 32

- ^ Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 130–133

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 105

- ^ a b Gravett Hastings pp. 29–31

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 52

- ^ Bennett, et al. Fighting Techniques pp. 21–22

- ^ a b c Lawson Boxing of Hastings pp. 183–184

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 114

- ^ Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 212–213

- ^ a b Gravett Hastings p. 91

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 101

- ^ a b Lawson Battle of Hastings p. 57

- ^ Lawson Boxing of Hastings p. 129

- ^ Freeman History of the Norman Conquest pp. 743–751

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 157

- ^ a b c d Gravett Hastings p. 59

- ^ a b Marren 1066 p. 116

- ^ a b Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 186–187

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 125–126

- ^ a b Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. twoscore

- ^ a b Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 190–191

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h Gravett Hastings p. 64

- ^ Hare Boxing Abbey p. 11

- ^ English Heritage Enquiry on Battle Abbey and Battlefield

- ^ Battlefields Trust Battle of Hastings

- ^ Lawson Battle of Hastings p. 192

- ^ a b c d e f g Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. 41

- ^ a b Gravett Hastings pp. 65–67

- ^ a b Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. 42

- ^ Gravett Hastings p. 68

- ^ a b c d e Gravett Hastings pp. 72–73

- ^ Marren 1066 pp. 127–128

- ^ a b c d Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. 43

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 130

- ^ a b c d eastward Gravett Hastings pp. 76–78

- ^ Marren 1066 pp. 131–133

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 135

- ^ Gravett Hastings p. 79

- ^ a b Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 207–210

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 138

- ^ a b Rex Harold II pp. 256–263

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 137

- ^ Walker Harold pp. 179–180

- ^ a b Gravett Hastings p. 80

- ^ a b c Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 217–218

- ^ a b c Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 130

- ^ a b Marren 1066 p. 152

- ^ a b Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 219–220

- ^ Walker Harold pp. 180–181

- ^ Quoted in Marren 1066 p. 152

- ^ Nicolle Normans p. 20

- ^ Rex Harold 2 p. 253

- ^ a b c Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 131

- ^ a b Gravett Hastings p. 81

- ^ a b c Marren 1066 p. 146

- ^ a b Marren 1066 pp. 147–149

- ^ a b Livesay "Skeleton 180 Shock Dating Result" Sussex Past and Present p. 6

- ^ Barber and Sibun "Medieval Hospital of St Nicholas" Sussex Archaeological Collections pp. 79–109

- ^ Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. 91

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 204–205

- ^ a b Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 205–206

- ^ Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest p. 45

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 212

- ^ Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest pp. 49–50

- ^ Bennett, Campaigns of the Norman Conquest, pp. 51–53

- ^ Bennett Campaigns of the Norman Conquest pp. 57–sixty

- ^ Coad Battle Abbey and Battlefield p. 32

- ^ Coad Battle Abbey and Battlefield pp. 42–46

- ^ Coad Battle Abbey and Battlefield p. 48

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 165

- ^ a b Coad Boxing Abbey and Battleground p. 31

- ^ Gravett Hastings p. 99

- ^ "Normans fight Saxons... and the rain". BBC News . Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Male monarch Harold and William square up". BBC News. 14 October 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

References

- Hairdresser, Luke; Sibun, Lucy (2010). "The Medieval Hospital of St Nicholas, Eastward Sussex: Excavations 1994". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 148: 79–110. doi:ten.5284/1085944.

- Barlow, Frank (1970). Edward the Confessor. Berkeley, CA: Academy of California Press. ISBN0-520-01671-8.

- Barlow, Frank (1988). The Feudal Kingdom of England 1042–1216 (Fourth ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN0-582-49504-0.

- Bates, David (1982). Normandy Before 1066. London: Longman. ISBN0-582-48492-8.

- Bates, David (2001). William the Conquistador. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN0-7524-1980-three.

- Battlefields Trust. "Boxing of Hastings: 14 October 1066". UK Battlefields Resource Centre . Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Bennett, Matthew (2001). Campaigns of the Norman Conquest. Essential Histories. Oxford, United kingdom: Osprey. ISBN978-ane-84176-228-9.

- Bennett, Matthew; Bradbury, Jim; DeVries, Kelly; Dickie, Iain; Jestice, Phyllis (2006). Fighting Techniques of the Medieval Earth AD 500–Advert 1500: Equipment, Combat Skills and Tactics. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN978-0-312-34820-five.

- Carpenter, David (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of U.k. 1066–1284. New York: Penguin. ISBN0-14-014824-8.

- Coad, Jonathan (2007). Boxing Abbey and Battlefield. English Heritage Guidebooks. London: English Heritage. ISBN978-ane-905624-20-i.

- Coredon, Christopher (2007). A Lexicon of Medieval Terms & Phrases (Reprint ed.). Woodbridge, Uk: D. Due south. Brewer. ISBN978-i-84384-138-8.

- Crouch, David (2007). The Normans: The History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN978-1-85285-595-6.

- Douglas, David C. (1964). William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. OCLC 399137.

- English language Heritage. "Research on Battle Abbey and Battleground". Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Freeman, Edward A. (1869). The History of the Norman Conquest of England: Its Causes and Results. Vol. 3. Oxford, Britain: Clarendon Press. OCLC 186846557.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, South.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (3rd revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Academy Printing. ISBN0-521-56350-X.

- Gravett, Christopher (1992). Hastings 1066: The Fall of Saxon England. Campaign. Vol. 13. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN1-84176-133-8.

- Hallam, Elizabeth Yard.; Everard, Judith (2001). Capetian France 987–1328 (2nd ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN0-582-40428-2.

- Hare, J. N. (1984). Boxing Abbey: The Eastern Range and the Excavations of 1978–80. London: English Heritage. p. xi. ISBN9781848021341 – via Archeology Data Service.

- Higham, Nick (2000). The Death of Anglo-Saxon England. Stroud, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Sutton. ISBN0-7509-2469-1.

- Huscroft, Richard (2009). The Norman Conquest: A New Introduction. New York: Longman. ISBN978-1-4058-1155-two.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN0-582-84882-2.

- Lawson, M. K. (2002). The Battle of Hastings: 1066. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN0-7524-1998-6.

- Livesay, Edwina (2014). "Skeleton 180 Daze Dating Result". Sussex Past and Present. 133: 6.

- Marren, Peter (2004). 1066: The Battles of York, Stamford Bridge & Hastings. Battleground Britain. Barnsley, UK: Leo Cooper. ISBN0-85052-953-0.

- Musset, Lucien (2005). The Bayeux Tapestry. Translated by King, Richard (New ed.). Woodbridge, Uk: Boydell Press. ISBN1-84383-163-5.

- Nicolle, David (1999). Medieval Warfare Source Book: Warfare in Western Christendom. Dubai: Brockhampton Press. ISBN1-86019-889-nine.

- Nicolle, David (1987). The Normans. Oxford, Uk: Osprey. ISBN1-85532-944-1.

- Porter, Roy (2020). Pevensey Castle. London: English language Heritage. ISBN978-1-910907-41-ii.

- Rex, Peter (2005). Harold 2: The Doomed Saxon King. Stroud, Uk: Tempus. ISBN978-0-7394-7185-two.

- Stafford, Pauline (1989). Unification and Conquest: A Political and Social History of England in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN0-7131-6532-four.

- Stenton, F. 1000. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thomas, Hugh (2007). The Norman Conquest: England later William the Conquistador. Critical Issues in History. Lanham, Dr.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN978-0-7425-3840-5.

- Walker, Ian (2000). Harold the Terminal Anglo-Saxon King. Gloucestershire, UK: Wrens Park. ISBN0-905778-46-4.

- Williams, Ann (2003). Æthelred the Unready: The Sick-Counselled King. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN1-85285-382-4.

External links

- Official English Heritage site

- Origins of the conflict, the battle itself and its aftermath, BBC History website

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hastings

Posted by: stinsonhavelf.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Long Was The Battle Of Hastings"

Post a Comment